BrasilAgro – Companhia Brasileira de Propriedades Agrícolas (NYSE:LND) is a land developer and farmer in Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia. The company currently owns about 215 thousand hectares, mostly in Brazil’s center and northeast.

The company has been paying dividends and offers a discount to net asset value of about 45% at current land valuations, sustaining a bull argument.

For a more detailed revision of the company’s assets, please visit my articles from December 2021, and October 2022. In those articles, I argued that LND’s land prices (and consequently NAV) and profitability were dependent on commodity prices that were at a local peak. Evaluated from cycle-average levels, neither the NAV nor the company’s profitability justified its valuation. For that reason, I recommended waiting.

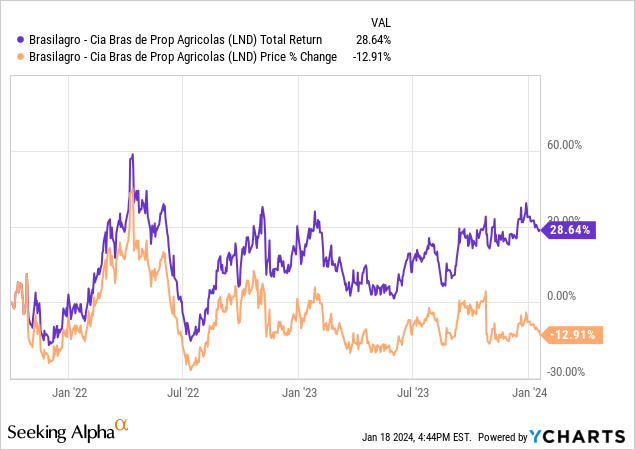

The chart below shows that since my first article, the return to shareholders has been good but not stellar. Further, the totality of that return was based on dividends as the stock price fell. Those dividends are based on land sales that, I argue later, are based on current high prices for commodities and therefore not sustainable under all scenarios.

In this article, I review the results from FY23. With commodity prices stagnant, the company has been unable to continue posting higher profits or land values. This, in part, confirms my previous article’s thesis.

In my opinion, the company does not offer operational or asset protection against a decrease in commodity prices. It is rather a speculative bet, akin to investing in a commodity ETF, with obvious differences like no futures management costs (positive) and political risks (negative).

Farming is only marginally profitable

BrasilAgro calls itself a land development company, not a farmer, and its farming operations have been profitable only during agricultural commodity bull cycles.

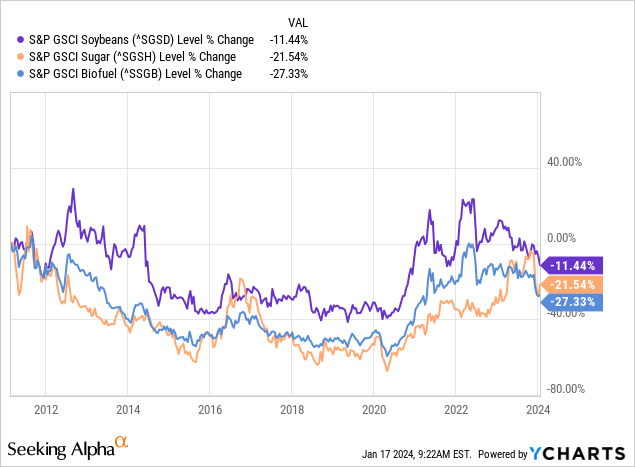

If we remove the effect of land sales from operating income, the company has only posted operational profits in 6 out of the past 14 years (2011, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022). This means the company was not profitable during most of the bearish cycle of its main crops, soybean and sugarcane, between 2012 and 2020.

This is common among commodity-producing companies, with only the lowest-cost producers being profitable under all market scenarios. However, it implies that if commodity prices were to move south, BrasilAgro could not provide income from its agricultural operations.

Land prices and development

At the risk of constructing a straw man, the bullish stance on BrasilAgro can be summarized mostly in the stock’s current discount to NAV.

BrasilAgro accounts for its land holdings in the balance sheet at acquisition cost but also provides a fair value table (Note 11 in FY23 financial statements). The land is valued at BRL 3.6 billion using fair value measurements.

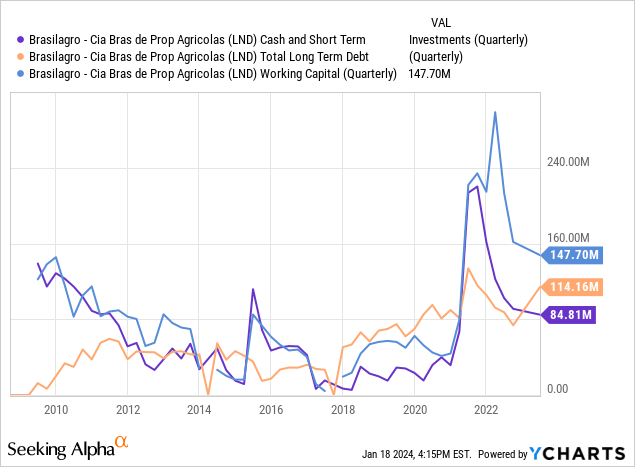

As the chart below shows, cash and short-term investments plus working capital minus long-term debt yield an additional $117 million (approximately BRL 600 million). This would be around BRL 4.2 billion in NAV ($850 million).

Another way of arriving at that level of NAV is simply adding the fair value difference of land to the company’s book value. The investment properties are accounted for at cost, or BRL 1.2 billion, but LND claims their fair value is BRL 3.6 billion. If we add the difference (BRL 2.4 billion) to the company’s BRL 2.2 billion in equity as of FY23, we arrive at a similar BRL 4.6 billion in NAV ($900 million).

If we compare that to the company’s current $500 million market cap, it trades at a 45%+ discount to this NAV. The bulls argue that BrasilAgro could continue selling land in order to finance its dividend.

Further, given that BrasilAgro is a land developer, maybe the increase in land prices could be attributed to their operations and therefore accounted as another source of operational income.

I don’t believe any of these arguments are true. In my opinion, both the NAV discount and BrasilAgro ‘s land development depend on the prices of the commodities.

BrasilAgro ‘s land fair value doubled between 2019 (financial statements) and 2023, from about $370 million to $730 million. Land sales of BRL 892 million between 2020 and 2023 approximately matched BRL 1 billion in land purchases, so the fair value difference is mostly price appreciation. A recent article by the University of Illinois shows that Brazil’s land prices doubled between 2019 and 2022, in line with the commodities bull market. All land in Brazil’s main producing regions and crops doubled in price, not BrasilAgro ‘s land alone, thanks to their land development efforts.

As a comparison, between 2012 (financial statements) and 2019, the value of BrasilAgro ‘s land went down, from about $400 million to $370 million, in line with the prices of sugar and soybeans.

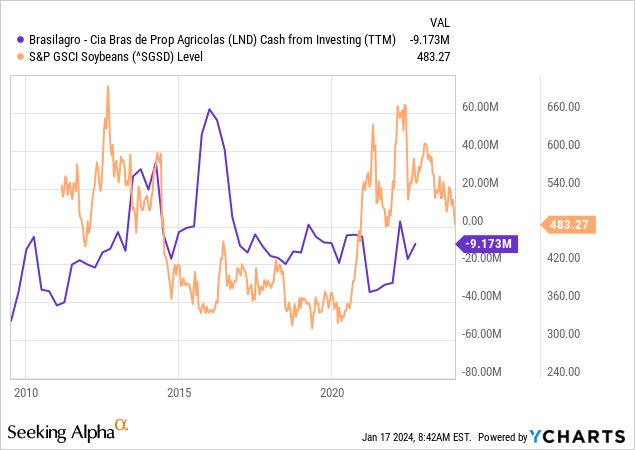

Another potential argument is that BrasilAgro may be an informed player in the land market, buying during bearish periods and selling during bullish ones. However, this does not seem to be the case. The chart below shows that the company purchased land cyclically (negative cash from investing during high prices, positive during low prices). The chart does not account for the almost $200 million in land purchases (financed by land sales mostly) between 2020 and 2023 that are buried inside cash from operations (a curious accounting decision).

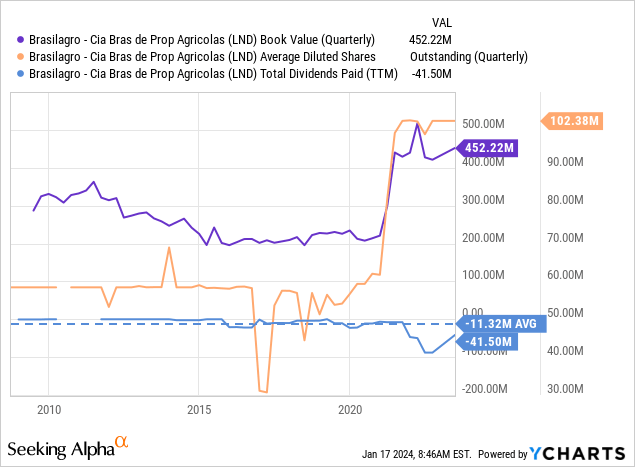

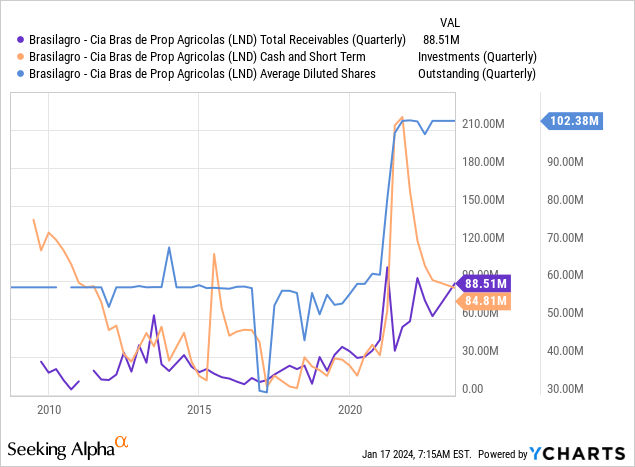

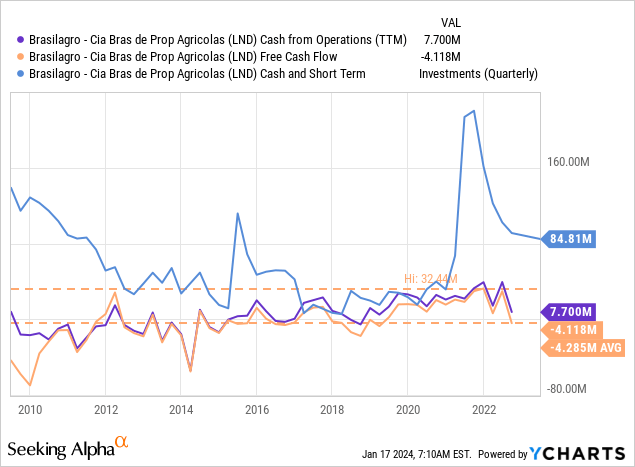

Finally, the result of good capital allocation is either the increase in book value per share organically or the payment of dividends. There is no other place where profits can go. However, as the first chart below shows, book value and dividends increased only after the company issued shares in 2020. Also, the company’s FCF or receivables change has not been enough to pay for the new dividends (second and third charts below) which I believe were partially financed via the proceeds from issuing shares.

Would LND’s solvency be at risk if the value of its land holdings fell? Probably not, given that its cash and short-term investment holdings approximately match the company’s total debt. LND should not need to sell land at low valuations if commodity prices fall.

Scenarios and valuation

We could think of two scenarios: an optimistic one where commodity prices remain elevated and a pessimistic one where they decrease.

Under the first scenario, LND could be considered cheap, which is why some writers are bullish on the name. The company could generate operational profits of $60/70 million, as it has averaged since 2021 (ignoring land sales). After interest ($15 million) and taxes (30% in Brazil), $40 million would remain.

We can see that even under an optimistic scenario (continuation of the bull cycle of commodities for the past 3 years), LND offers a relatively high P/E ratio of 12x (considering a $500 million market cap). But, theoretically, an investor could buy the company for $500 million, sell 70% of the land to pay himself a $500 million dividend, and get the remaining 30% of the land, plus all assets, for free. By slowly selling land and paying dividends, the company follows this idea.

However, under the pessimistic scenario, LND cannot produce much profit. Between 2014 and 2020, it averaged operating profits of $18 million, barely covering current interest expenses. The P/E ratio, in this case, is extremely high ($500 million for less than $5 million in income per year). Further, the value of land (as evidenced by fair valuations provided between 2012 and 2019) could not cover the purchase price of the company and then some.

This, in my opinion, is when a company is priced optimistically. Only if the favorable scenario happens there is a gap between price and value. If the pessimistic scenario ensues, the gap disappears, and the price paid is above the value obtained.

In my opinion, an exciting commodity company provides some margin of safety. Either its assets are significantly discounted (and not correlated to the commodity price) or can produce a sufficient profit during bear cycles. I also like these companies to invest countercyclically as much as possible and to buy them during the bearish portion of the cycle.

BrasilAgro does not offer any of these characteristics. It cannot produce commodities profitably (or only marginally, as in 2018 and 2019) if prices are depressed, the discount to assets is correlated to commodity prices, and it has not invested countercyclically or grown shareholder value.

I don’t know where commodity prices are heading, but they are high compared to the previous decade, so it’s difficult to call the current period a bearish portion of the cycle. This means that in the future, I believe a decrease and not an increase in commodity prices is more likely.

However, my thesis is not based on a directional call on commodity prices but on how those prices relate to LND’s value. I want a company that offers a “tails I win, heads I don’t lose much” proposition. LND is not such a company because it can only offer value if commodity prices remain high. For that reason, I don’t recommend it.

Read the full article here