About the author: Desmond Lachman is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was previously a deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney.

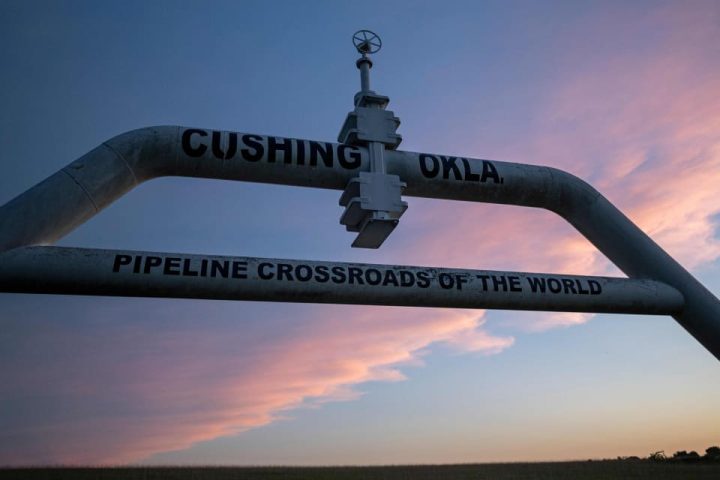

Heightened geopolitical tension is raising the risks of an oil shock at a challenging moment. The world’s major central banks’ task of regaining inflation control is far from done, and the world economy is slowing. But that is only part of the picture. The recent spike in long-dated U.S. Treasury bond yields and a prospective wave of commercial real estate loan defaults are causing strain in the U.S. banking system.

So far international oil prices have been well-behaved, trading in a range of $85 to $90 a barrel, despite the outbreak of what is expected to be a long war between Israel and Hamas. However, if that war were to spread to the rest of the region including Iran, oil prices must be expected to spike to well above $100 a barrel.

Oil could surge to above $130 a barrel if attacks on energy infrastructure were to disrupt physical supply, according to Bank of America. But the shock could be far more severe. Were supply to fall by two million barrels a day, prices could rise above $150 a barrel.

Energy markets are still adjusting to the disruptions from the war in Ukraine. That heightens the risks from the Middle East conflict, as the World Bank says in a new report today. “If the conflict were to escalate, the global economy would face a dual energy shock for the first time in decades,” warns Indermit Gill, the World Bank’s chief economist.

An oil price spike would quickly lead to higher gasoline prices at the pump. That would increase headline inflation, which in both the U.S. and Europe is already running well above their central banks’ 2% inflation target. It would also negatively impact investor confidence and reduce aggregate demand by constituting an effective tax on consumers who are already having to cope with mortgage and automobile loan interest rates of some 8%.

According to the International Monetary Fund, if sustained, a 10% increase in oil prices would reduce global economic growth by 0.15% and increase global inflation by 0.4%. That implies that if oil prices were indeed to rise to $130 a barrel, world gross domestic product could be lower than it otherwise would have been by around ¾ of a percentage point and world inflation could be two percentage points higher.

The prospect of stagflation, the combination of inflation and a weak economy, would put both the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank in an unenviable position. Higher inflation would make it difficult for these central banks to reduce interest rates without risking a further loss in their inflation fighting credibility. Yet not reducing interest rates would risk inviting a recession at a time that the economy would be being hit by an oil price shock and by uncomfortably high long-term borrowing rates.

A slowing economy would also heighten the chances of a U.S. and world financial crisis. Even before the latest geopolitical tension, U.S. and European banks’ bond portfolios were being severely damaged by the spike in long-term interest rates and the corresponding battering of bond prices.

The banks were also facing the prospect of a wave of commercial property loan defaults. Property developers have to cope with low occupancy rates in a post-Covid world and must roll over $500 billion of maturing loans next year at very much higher interest rates than those at which the loans were originally contracted. Slowing economic growth would potentially take them from bad to worse by raising the incidence of defaults on all their other lending.

For many reasons we must hope that the Israel-Hamas conflict is soon resolved without spreading to the rest of the Middle East. However, hope is not a strategy. Rather, the world’s central banks should have contingency plans for the eventuality that a spike in oil prices could be the last straw that triggers a world economic recession and precipitates a world financial crisis.

Guest commentaries like this one are written by authors outside the Barron’s and MarketWatch newsroom. They reflect the perspective and opinions of the authors. Submit commentary proposals and other feedback to [email protected].

Read the full article here