Those who can, pay cash to avoid the interest rates. Subprime credit tightens substantially.

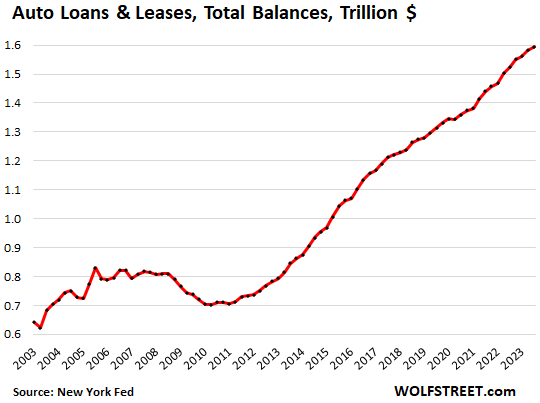

The balance of auto loans and leases rose by 0.8% in Q3 from Q2, and by 4.7% year-over-year, to 1.60 trillion, driven by financing of new vehicles, according to data from the New York Fed’s Household Debt and Credit Report.

New vehicles account for the bulk of the auto loans and leases. New-vehicle prices still rose in Q3, and new-vehicle unit sales jumped 20% year-over-year. So that’s where the increase in loans and leases came from.

By contrast, used vehicle prices have been falling since the ridiculous spike through 2021, and retail sales of used vehicles in Q3 were roughly flat year-over-year. Used vehicles are not contributing to the increase in auto loan balances.

More buyers pay cash. The much higher interest rates make borrowing unattractive. With new vehicles, automakers’ captive finance units are buying down interest rates to 1.9% or whatever. But this is an incentive in lieu of cash incentives, such as a big rebate, that cash buyers get. And so the percentage of cash buyers has risen this year for both new and used vehicles.

About 20% of new-vehicle buyers and about 61% of used-vehicle buyers paid cash for their auto purchases, according to Experian’s Q2 report on auto finance, up from 16.5% and 58.5% respectively a year earlier. And these buyers have no debt burden associated with their vehicle.

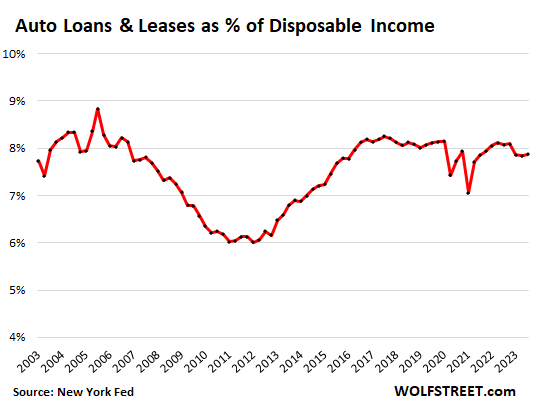

The debt burden fell this year. In terms of the aggregate debt burden, total auto loans and leases outstanding amounted to 7.9% of total disposable income, a tad below where they’d been during the Good Times before the pandemic.

Disposable income is income from all sources except capital gains, minus taxes and social insurance payments. This is the cash that consumers have left to spend on, for example, cars.

The fairly sharp drop in the debt burden ratio this year was due to the increased portion of cash buyers along with the biggest pay increases in 40 years:

Credit has tightened substantially for subprime. The part of auto lending that is seeing tighter financial conditions is subprime lending. Loans are harder to get, some of the most aggressive lenders/dealers have filed for bankruptcy, and other lenders have tightened their subprime underwriting. Losses lead to more prudent underwriting, which eventually leads to fewer losses. This is part of the subprime cycle.

So the share of subprime as a percent of total financing has dropped. According to Experian’s Q2 report, subprime’s share of total originations of loans and leases dropped to 15.0%, down from 16.8% a year ago, and down from 17.8% two years ago.

Prime borrowers have no problems financing or leasing a vehicle, but the cheap money is gone.

Borrowers pay out of their nose: According to data from commercial banks collected by the Federal Reserve, the average interest rate for 72-month new vehicle loans has spiked from 4.84% in February 2022, before the rate hikes started, to 8.12% in August 2023.

But it’s less shocking than it seems. For example, for a $40,000 loan at 4.84% for 72 months, the payment was $642 per month; at 8.12%, the payment is $704. I can already hear it: “Just $62 a month more, and you get your dream.” And people want their dream.

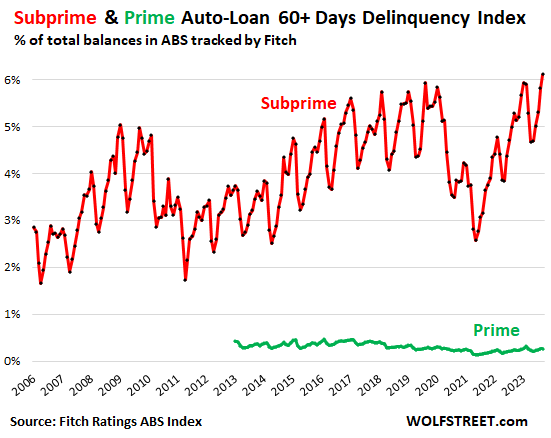

Delinquencies are driven by subprime. Subprime is always more or less in trouble. That’s why it’s subprime. In the auto loan market, selling and lending to customers with subprime credit ratings is a high-risk high-profit specialized activity, largely limited to older used vehicles. It has attracted a bevy of specialized lenders and dealers, often backed by PE firms. The system hinges on being able to securitize the subprime auto loans into Asset Backed Securities (ABS) and sell the investment-grade tranches of those ABS to pension funds and other yield-hungry institutional investors at relatively low yields, and that works until it doesn’t, and now it doesn’t.

A number of those ABS deals got scuttled recently, and some got pulled off only after they’d been renegotiated, and several of those specialized operations have filed for bankruptcy, and we covered a couple of them here.

There’s a peculiar subprime cycle, where low yields enticed specialized companies to get very aggressive and take huge risks, backed by yield-starved investors that buy the ABS. But after a while, because those deals were too aggressive, the risks come home to roost, and investors are taking losses, and they’re getting skittish, and the whole math sort of begins to unravel. That happened in 2018, and it’s happening again.

But subprime is only a small part of the auto-lending business, and an even smaller part of the auto-sales business because lots of people pay cash. Of those buyers that finance new vehicles, only about 5% are subprime; and of those that finance used vehicles, 22% are subprime, according to Experian.

And subprime loans that are at least 60 days delinquent spiked through September (red line). But prime loans are rock-solid with minuscule and stable delinquency rates that are below where they’d been before the pandemic, according to the auto loans backing the ABS that are tracked by Fitch Ratings:

The overall delinquency rates of auto loans and leases are always fairly high, compared to mortgages, but are below the delinquency rates for credit cards.

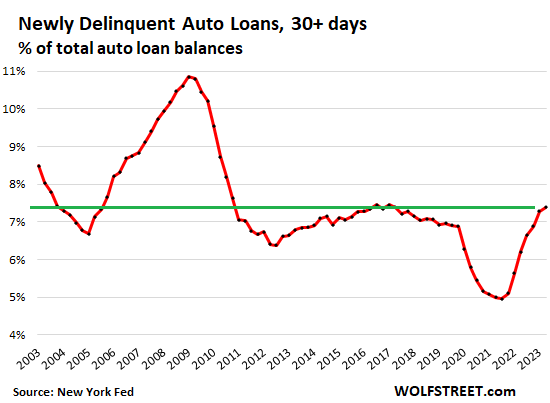

Auto loans and leases that just transitioned into delinquency by the end of Q3 inched up by 11 basis points – the slowest increase since they started increasing in Q1 2022 – to 7.39% from 7.28% in the prior quarter. So they’re roughly back in the normal range:

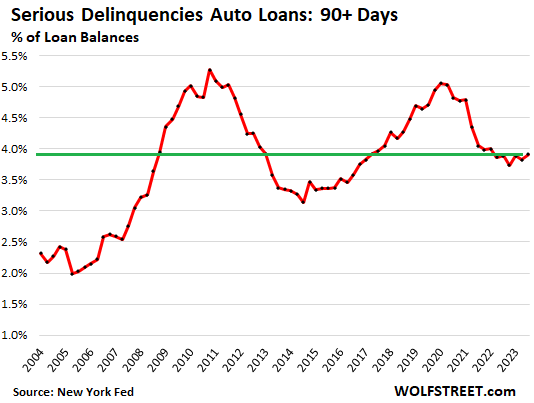

Auto loans that were seriously delinquent – 90 days or more past due by the end of Q3 – barely ticked up in Q3, after dropping in Q2, and are relatively low, compared to the past 15 years:

Earlier on Tuesday, we were wondering, “where’s the hangover from the party?”

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here