At the end of 2022, I published a bearish outlook on the mining giant Vale S.A. (NYSE:VALE) in “Vale: Margins Under Pressure As Energy Shortage Increases Costs And Impairs Demand.” At that time, I believed the stock would lose some value due to rising input costs and stagnating demand for metals, particularly from China, resulting in lower profit margins. This outlook has largely proven correct, albeit slower than I expected, as energy prices have declined. VALE has declined by ~21%, seeing its operating margins fall by around 5%

At the time of writing, the consensus surrounding VALE and mining was bullish, stemming from the strong inflationary rebound the sector faced after the lockdowns. Today, most analysts and investors have a mixed outlook, with the stock receiving an average Wall Street rating of 4.04, right between “buy” and “hold.” To generate alpha, we’ll typically need to be more accurate than the consensus, so keeping the mildly bullish sentiment surrounding VALE in mind is vital.

To a great extent, the pattern I saw developing around the end of 2022 remains today. That is lower demand from China and numerous rising cost factors. Of course, key changes to Western economies may significantly impact Vale’s profits. Additionally, large shifts in geopolitical developments may benefit or weigh on Vale. Thus, I believe it is an opportune time to provide an updated outlook on the company.

All Eyes on China’s Construction Sector

Some of the bullish sentiment surrounding Vale focuses on copper, nickel, and other metals that are expected to see long-term demand growth due to green infrastructure development needs in Western economies and most of the world. While this factor should be considered, copper demand growth is only rising at 2-3% per year, and a massive portion is used in China’s market. Further, in 2023, copper only accounted for $2.4B of Vale’s $41.8B net operating revenues. Conversely, iron ore accounted for $34B, making it the most essential portion of its business. Additionally, $18.1B of its adjusted 2023 EBITDA came from iron ore. Still, its net adjusted EBITDA was $17.9B, indicating it is losing money on its other businesses (copper net EBITDA was $1.1B).

Most of its revenue and production is in Brazil, though it operates in Canada, Indonesia, and elsewhere. Crucially, 52% of its net operating revenues were sales to customers in China. According to the company, China accounted for 77% of the global demand for iron ore, 62% of global nickel demand, and 56% of copper demand. So, while we can consider the long-term potential of the metals market, Vale’s one to five-year income expectations are highly determined by Chinese demand. For the most part, stocks are priced according to shorter-term income expectations.

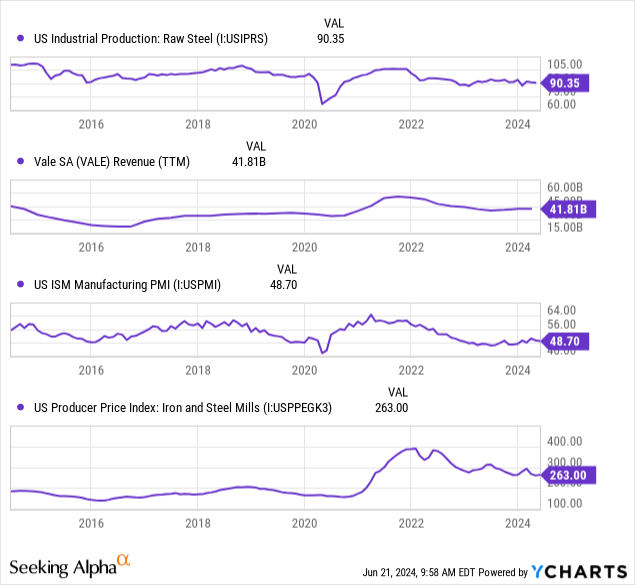

There is a decent correlation between Vale’s revenue, iron and steel mill producer prices, the US manufacturing PMI, and US steel production. Again, most of Vale’s products are going to China. However, weakness in the US almost always causes weakness in foreign manufacturing markets. See below:

Coming out of 2020, I argue that meager interest rates and inflationary stimulus policies in Western economies led to a substantial artificial spike in manufacturing demand. I say artificial because I do not think the manufacturing PMI and US steel production would have been so strong in 2021 and 2022 if not for global central banks’ interest rate cuts, QE, and deficit spending programs that boosted economic demand far above supply levels (leading to inflation).

As prices rose in 2022, this trend reversed, with the manufacturing sector entering a persistent downturn, as indicated by falling steel production and the under-50 manufacturing PMI. My outlook for Western economies is decidedly negative, as I believe there is strong evidence to suggest unemployment may soon rise faster.

In my opinion, China’s economy, which is extremely important for Vale, is in worse condition, although its government has more strings to pull. China’s core issue centers around its property market. After decades of supporting the price bubble through various means, the country has home price-to-income ratios of around 30X. Many people in China use real estate, not stocks, as a store of wealth, giving it a homeownership rate of 90% (according to debatable official government statistics.)

Over a decade of extremely high property prices has caused immense overdevelopment, giving it a vacancy rate of 20% in urban areas and 40% in rural areas. Its office vacancies are also in that range. Notably, the Chinese government is keen on keeping these facts secret, as seen by a 2022 scandal after a property firm published very conservative vacancy estimates in China.

Frankly, China’s property market bubble makes the 2008 US property bubble seem like a value opportunity. Vacancies peaked at ~3% in the US in 2007, with the price-to-income median peaking at ~5X (though it is closer to 6X today). No doubt, after creating so many empty cities, the bubble cannot grow forever. Remember that China’s population is falling rapidly, so demand will not rise soon.

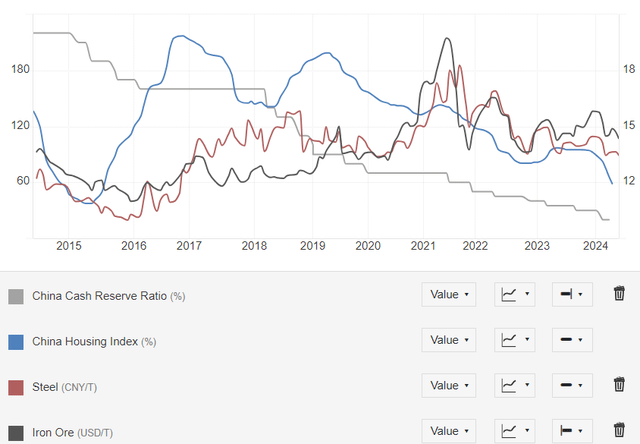

Since construction accounts for a large portion of China’s employment and real estate is a massive portion of household wealth (70% to 80%), the CCP is desperate to keep this bubble from popping. Its primary means of stopping it is lowering the bank cash reserve ratio, to encourage more mortgage lending and boost additional home demand. This strategy of solving a debt crisis with more debt is tragically common and rarely ends well.

This approach worked well for most of the 2010s but has not worked well since 2020. The country has cut the reserve ratio faster but has not managed to boost housing prices as it had in the past. Crucially, we’re not seeing iron ore and steel rebar prices mirror the trend in China’s home prices. See below:

China property bubble vs. iron and steel prices (TradingEconomics)

In my opinion, investors should view the Chinese government’s economic commentary with extreme skepticism. Given how its population is closely tied to the real estate sector, its government has little reason to be completely truthful regarding its ability to manage the situation. Given its home prices are falling at an accelerating pace despite accelerated stimulus efforts, I believe it is a virtual certainty that its property development market is in collapse.

I do not say collapse lightly. I am sure some construction will continue in China, but given its high widespread vacancies, there is essentially zero need for continued office and residential development. I believe there will never again be a significant need, given its population should not rise to meet vacancies within the coming 50+ years (outside of immigration, which China is not known for).

Housing starts in China peaked in 2019 at around 227K square meters (peak season). At the 2023 seasonal peak, housing starts were at 95K, its lowest level since 2007. China’s property investment is falling at nearly 10% annually and has stagnated at a rate of decline since November of 2022. More than 50 Chinese property developers have defaulted since the Evergrande crisis, and I expect that number will rise as it becomes more apparent that the CCP’s “reform” (or, to me, “kick the can down the road”) efforts will not work. I believe the recent default of its largest developer, Country Garden, is likely a catalyst for much greater industry failure.

In my opinion, we cannot separate Vale from this issue. Chinese demand for construction steel has been the company’s primary sales driver in recent decades. No country’s iron ore imports are remotely close to China’s, so even if global demand doubled while China’s halved, the net change in demand would still be negative. I argue that a great deal, if not most, of that iron is going to large buildings that will never be occupied. Thus, as we continue to see Chinese developers fail and prices fall, I believe iron ore demand will plummet and likely remain low for over a decade.

In Vale’s Q1 investor call, a manager pointed to “China resiliency,” which I believe is not supported by evidence and only by the CCP’s ever-positive commentary. That said, in its Q4 call, the company pointed to growth in its ex-China market. In the long run, I agree that ex-China could see growth as many developed countries have some infrastructure redevelopment needs. That said, steel demand is falling in Western countries due to economic weakness. Thus, while I think copper’s high price will give some support, I do not expect stability in its iron ore market for many years.

Vale’s managers have also pointed to growth in Middle Eastern demand as a positive catalyst. I feel Saudi Arabia’s (and peers) construction concepts are perhaps worse than China’s (see $1.5T urban planning nightmare.) Yes, these trophy projects may temporarily aid iron demand, but, to me, they’re not the projects of governments looking for sustainable and fruitful development.

How Low Can Vale’s Income Go?

In my view, Vale’s macroeconomic outlook is worse today than in 2022, aside from energy costs. My outlook for Chinese construction steel demand remains the same, but I think that far more analysts and investors agree with me today than they did then. Back then, it seemed more people took to the view that China’s communist power could somehow keep a bubble growing forever. Indeed, I’d argue their efforts to prolong the bubble have only worsened the crisis. Further, I think it is clear that the US, Europe, and Japan will not see strong steel or iron demand growth anytime soon. Yes, electric vehicles should benefit from copper, but copper accounts for very little of Vale’s overall sales.

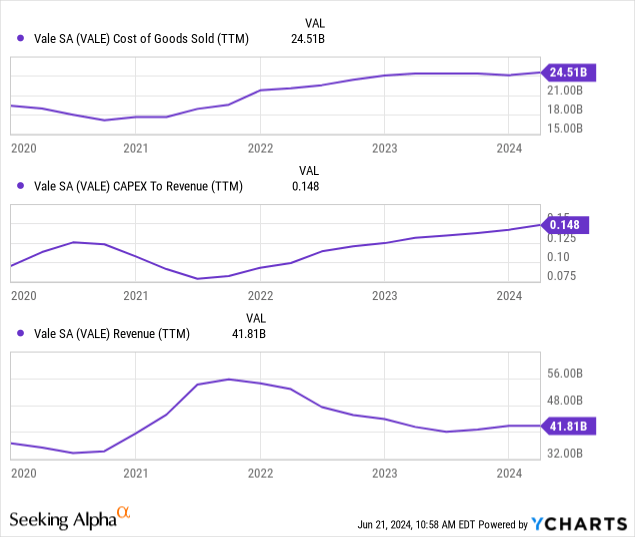

Problematically, I think Vale’s operators are in denial regarding the extent of this issue. They’re seeing sales decline despite efforts to shift away from China. Further, its COGS is rising and may accelerate due to sticky inflation. The Brazillian Real is weakening quickly, theoretically benefiting Vale by lowering relative labor costs. However, I’d argue that the pace of the Real’s decline is not good as it could result in political instability and uncontrolled inflation, such as in Argentina and Turkey.

Vale is not reducing its CapEx spending despite clear signs of macroeconomic weakness. See below:

I believe Vale should be looking to store up cash to offset risks from a likely prolonged decline in its profit margins and sales. Instead, it continues to invest in growth, which there is little immediate (and likely future) global economic demand for. The company’s financial debt is ~$16B, which should be noted, though it is half its 2010s levels. However, its working capital was just $1.85B at the end of Q1, which ranges toward the low end of its past levels, giving it little extra liquidity.

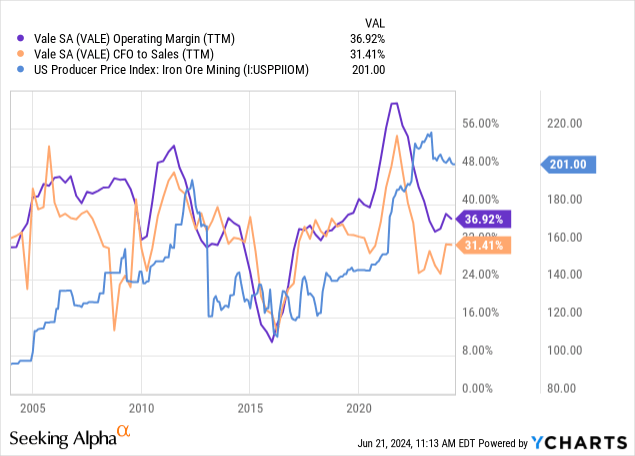

I continue to expect the profit margin shock from the combination of falling demand and rising costs to result in operating margins below 20%. The company has faced such declines in years past, such as the short-lasting Chinese property market slowdown in 2014. In the past two decades, it has not faced as significant an issue as I expected, given that the past two decades have typically seen inordinate growth from China. See its margins vs. US iron mining PPI below:

Of course, if oil prices rebound, as I suspect they may, then Vale’s profits could be even lower. Most fuels are stagnant and might remain as demand falls, but the energy market’s supply issues may still push prices up. Energy costs are a considerable portion of mining costs, which would be quite bearish for Vale.

The consensus EPS outlook for Vale is weak but potentially still overestimated. Analysts expect Vale’s EPS to be ~$2.30 this year and fall to $1.64 by 2028. I expect its operating profits will converge toward $8.5B (a 20% margin). Extrapolating its $770M net interest expense, we come to a pre-tax profit of ~$7.7B, or about $5.65B post-tax. It has some minority interest costs, so I project its earnings for common shareholders at ~$5B or an EPS target of $1.17. I expect its 2024 EPS will be above that, but its EPS should be closer to $1 for 2025 and beyond, depending on how large China’s bubble burst proves.

The Bottom Line

Thus, my outlook is below that of most analysts, but I do not currently expect it to have negative net income for a prolonged period. Its “P/E,” based on my EPS estimate, is around 10X, which is a reasonable figure for a cyclical mining company. Still, I think Vale could go lower when we account for its low working capital, high CapEx spending (despite sustained macro declines), and the risk that China’s bubble will have a hard landing. Thus, my outlook on Vale remains slightly bearish.

Although I do not believe it is considerably overvalued, I think it should trade at a considerable discount because it is racing into unprecedented territory. In my view, investors, analysts, and Vale’s managers are all very used to the “China growth” paradigm that has dominated the metals market since the 1990s. Now, we’re seeing incredible overdevelopment, with so much of that metal going to useless buildings.

In my view, there is considerable risk that global iron demand will decline and remain low for many decades as global population growth slows and more countries reach maximal urbanization. More skyscrapers are not needed in most of the world, and more steel is recycled, meaning iron ore demand has reached a permanent peak and may decline for decades. This view is speculative and is not currently widespread among analysts. However, as we see the impact of China’s property crisis over the coming year, I expect it may cause more questions about how Vale can transition to a post-industrialization global economy.

Read the full article here